INTRO.

- About Emily Dickinson on [wiki.]

- [Emily Dickinson Museum]—a wonderful tour of her house in Amherst, MA you should take.

- Someone please [buy me this 3 tome Franklin Edition] of Emily’s poems!

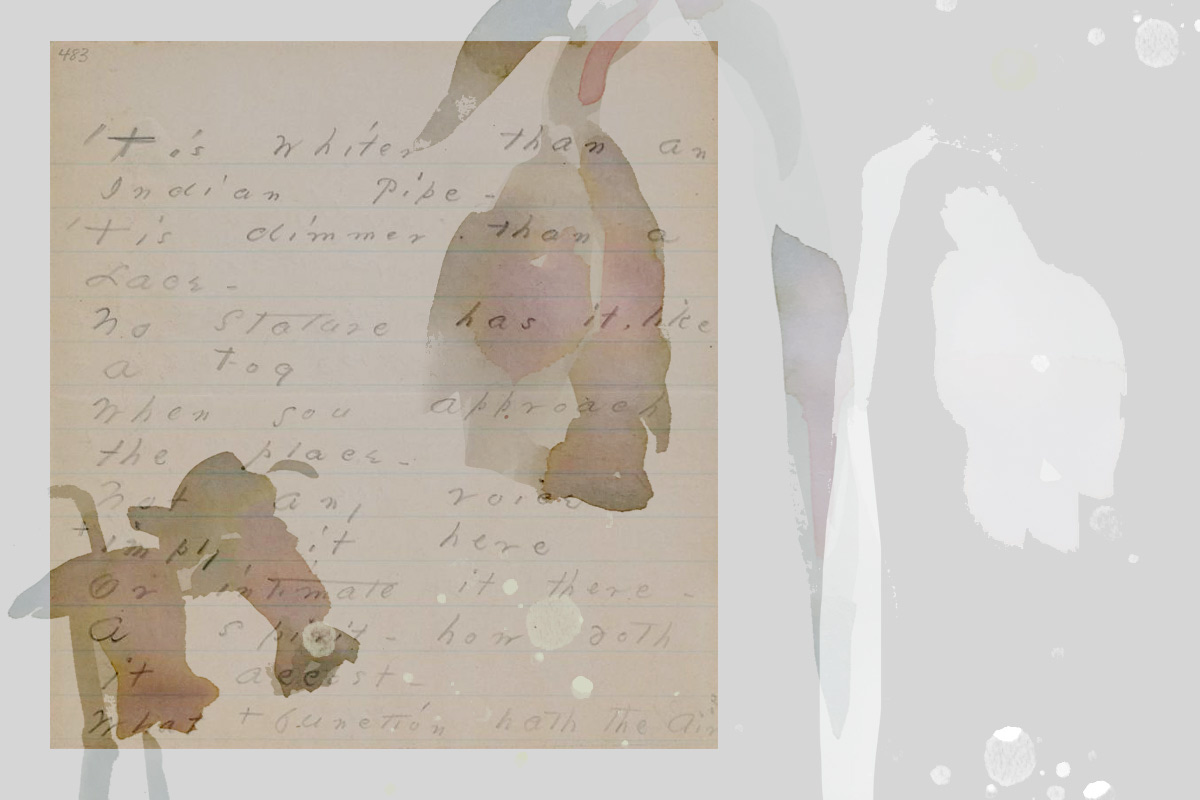

- Or better yet — [these Manuscripts], please please, please.

Looking into Emily’s life and horoscope, I see her unwavering connection to family, land, and heritage—a constant pulse in her Natal Chart where everything unfolds. She’s also among those who gained recognition only after death, a fact that nudges me, curiously and a bit morbidly, to explore her transits after she stopped pacing her father’s house in Amherst, MA, in that white-laced dress.

Sun—Snake Tamer—

When Emily writes :

But never met this fellow,

Attended or alone,

Without a tighter breathing,

in her poem “A narrow Fellow in the Grass”, she is the Sun in Ophiuchus (God of Invocations), conjoint by the star Sabik. As per Robson [**Fixed Stars and Constellations in Astrology, 1923**], Sobik with Sun gives a person sincere, honorable, scientific, religious, and philosophical interests, unorthodox or heretical, moral courage. [Robson, p.199.]

The astrological influences of the constellation Ophiuchus (Serpentarius, the Serpent-holder, the Serpent Bearer, the Serpent Wrestler, or the Snake Charmer) is said to give a passionate, blindly good-hearted, wasteful and easily seduced nature, unseen dangers, enmity, and slander. Pliny said that it occasioned much mortality by poisoning.

Emily, though, tames that snake (via her dipping pen?) and charms us with her unorthodox puzzle words. Susan Dickinson wrote about her friend: “A Damascus blade gleaming and glancing in the sun was her wit.”

Now, listen:

Ophiuchus, or Serpentarius, the Serpent-holder, the Serpent Bearer, the Serpent Wrestler, or the Snake Charmer, is depicted holding a snake, the snake is represented by the constellation Serpens. The constellation is located around the celestial equator with the two legs of Ophiuchus protruding right into the zodiac and south of the ecliptic. Ophiuchus is identified with Aesculapius (Asklepios, Asclepius), an ancient physician who grew so skilled in the craft of healing that he was able to restore the dead to life. However, because this was a crime against the natural order, Zeus destroyed him with a thunderbolt. According to one version (Pindar’s) he offended Zeus by accepting a fee in exchange for raising the dead (—my emphasis).* Ophiuchus is identified with

the God of Invocation. [here]

I find it remarkable that Emily’s poem, which seems to raise the dead within us through the “Fellow in the Grass,” is tied to her deep disdain for profiting from her work (***).

So, no, Zeus (Emily’s Jupiter is in the Fall), she didn’t profit.

Sun is also a midpoint of her Mars and Saturn. It is the fulcrum (Sun) of Emily’s (House 1 in Scorpio) writing (House 5 in Aries) and late / post-mortem publishing (Saturn on Midheaven) thanks to the commitment and work (Saturn) of her neighbors (Saturn ruling House 3).

Misfit—Mercury—Dashes—

As Emily paces the house, she scribbles on torn papers, chocolate wrappers, and jagged envelopes. Baking or wandering the foggy land, she tucks fragments of poems into her pockets, returning later to her room where she marks X’s for possible word alternatives.

This restless search for expressive expansion is her Mercury in Sagittarius—a misfit, always editing itself, exploring unusual forms. Who but Mercury in Sagittarius would pen alternate endings, just in case?

Her EmDash, like a whip, slices through her lively thoughts. It channels her Mars-Pluto conjunction’s fierce momentum, all square to her Part of Profession, with Mercury’s antiscia landing there and on her Part of Fortune.

Mercury, though combust, is heliacally rising, eager to act—write, document—despite Sagittarius's boundless contrast. With a trine to Midheaven, its eccentric expression effortlessly finds a home in her work.

With her Sun in Sagittarius, embodying the mythic Chiron—wounded, yet freeing Prometheus—Emily's life story feels like a grand exchange: Mind meets Heart, Intellect meets the world. Sun joins with Venus and Mercury in this cosmic trinity, squaring her Lot of Daimon/Spirit, ruled by Mercury the writer, the bridge, the misfit. This tension demands expression; there’s no escaping it.

Father—as Fuel—

The Sun doesn’t love mingling with Mercury; Mercury’s wild, unpredictable. But in Emily’s chart, it must. This conjunction likely sparked tension in her life—especially with her father, who fueled her mind yet kept boundaries. Her intellectual father brought her books, but Emily often pushed back, longing to expand her literary world with Wuthering Heights and more. So, perhaps, the Sun and Mercury argued, just as they did.

Heart—Moon—Mother—Poetry—

One of Emily’s most intense, challenging aspects is her Moon square Neptune. It reflects the lifelong tension with her mother—detached, melancholic, and often distant. This aspect manifested physically in her mother’s illness, a weight Emily bore for much of her life.

Emily’s mother died on November 14, 1882. Five weeks later, she wrote

We were never intimate … while she was our Mother – but Mines in the same Ground meet by tunneling and when she became our Child, the Affection came.

Yet, we might consider that her mother’s illness kept Emily home, fostering her writing—a gift wrapped in disguise (Moon/Neptune through Moon/Mercury).

With her Moon in Libra, she craved intellectual nourishment, and ultimately, she received it. However, Neptune in Capricorn isn’t a cozy home for her Moon. It creates a turbulent pull toward her mother—a relationship that both entangles and frustrates her, blurring boundaries. This is why her Moon seeks separation, striving for autonomy. The only way to carve out that space was to retreat into a single room, becoming a hermit. In that sanctuary, escapism flourished; she rarely ventured out, often only standing at the foot of the stairs to converse with those below (Moon in H12).

Born under a waning moon phase with a Moon in Via Combusta, slow and Void of Course, Emily’s Moon embodies constant reinvention and restless dissatisfaction. It’s that 9 PM feeling of retrospect—anxiety over another day passed with unresolved ambitions. Her Moon is perpetually pulled into questioning and confusion, grappling with her duty to her mother and an overwhelming desire to break free.

But clearly, in the chart, we can see that the only way to act out this Last Quarter Moon and its Neptune/Jupiter square is through work (Moon sextile MC, Mercury trines MC).

Jupiter—Self Worth—Creativity—

This sensitive, intellectual Moon must also navigate the complexities of Jupiter in the fall. At the heart of this tension lies her fragile self-worth (H2) and creativity (H5), which she channels into her writing while questioning the value of her poetry and her existence.

Jupiter, like Mercury, is an odd duck, nestled alongside Neptune, further complicating matters with a mother who becomes an unintended (spiritual) mentor. Despite the tumultuous love/hate dynamic with her mother, Emily writes fervently, pouring her emotions onto the page. This creative outpouring unfolds in her house of communication and neighbors (H3), where she shares her innermost thoughts through poetry and heartfelt letters to her beloved sister-in-law, who lives just a yard away.

God—Moon—Mercury—

In [“Mystical Prayer”] Charles M. Murphy:

explores the still unfolding rediscovery of Emily Dickinson (1830–1886), our foremost American poet, as a mystic of profound depth and ambition. She declined publication of almost all of her hundreds of poems during her lifetime, describing them as a record of her wrestling with God, who, in the Puritan religious tradition she received, she found cold and remote. Murphy places Dickinson’s writings within the Christian mystical tradition exemplified by St. Teresa of Avila and identifies her poems as expressions of what he terms theologically as “believing unbelief.” Dickinson’s experiences of love and her confrontation with human mortality drove her poetic insights and led to her discovery of God in the beauty and mystery of the natural world.

In 1845, the so-called Second Great Awakening took place in Amherst, a religious revival, resulting in many confessions of faith among Dickinson’s peers. The following year, Emily wrote:

I never enjoyed such perfect peace and happiness as the short time in which I felt I had found my Savior.

but this stimulation didn’t last; she never declared her faith nor attended church religiously. In a 1952′ poem she writes:

Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – I keep it, staying at Home –

Moon in H12.

Emily draws upon the Moon's power, seeking intellectual security in her quest for God. In her pursuit of proof—often elusive—she grapples with the burden of Neptune's weight on her shoulders.

God (Cancer/Moon in Libra, with Mercury as the lord of Placidus H9) is understood through her writing, connecting with friends via letters (H3, where Mercury resides, and H11, which he rules), along with her Venusian Sun. She attempts to articulate the divine, assembling words into poems.

Yet, this Moon operates from a hidden place (H12), creating a sense of alienation and neurosis. God feels distant, uncomfortable, and perplexing; understanding Him through the Mind proves futile without trust, which she struggles to find (thanks to Neptune's challenges).

The Moon-Neptune-Jupiter aspect forms the strongest dynamic in her chart, propelling her to craft metaphysical poetry in her upstairs sanctuary, where she dissects her existential dilemmas while gluing dried flowers into letters.

Emily's Last Quarter Moon in Via Combusta—the "burning way"—heightens her emotional turbulence. This passage between 15º Libra and 15º Scorpio, where both luminaries fall and both malefic reign, signifies ancient rites of purification, menstruation, funerals, and necromancy. Having her Moon here opens the gates to the divine or the underworld, but it's far from a gentle, sentimental journey; it’s a complex, often tumultuous experience.

Emily’s necromantic inclinations are evident in her fascination with death, especially as her house overlooks Amherst’s burial ground, and the phase of the Moon brings in the crisis within the increasing darkness of the Moon, where life comes to an end when something must die to be reborn, where Emily searches for God within puzzles (literally) of her words, asking and pleading until the Sun comes.

This mind-driven Moon fights for knowledge (and proof) and doesn’t go to church to sit politely and repeat prayers as the Pharisees do.

She wants to reach for God via her intellect and only through her merciful rewriting of her verses in that hidden room upstairs, where her quiet spiritual turmoil happens, she reaches her sermon:

I know that He exists. Somewhere – in silence –

Home—God—Teacher—Saturn—

Saturn is the most advancing planet in her chart, angular in Placidus. It embodies her heritage (4th House), her letters to neighbors like Susie (11th House), and her poetry (3rd House). Yet, Saturn also represents the father figure and older male influences in her life—Benjamin Franklin Newton, her academic principal, Leonard Humphrey, and literary critic Thomas Wentworth Higginson. While her father provided her with books, these mentors shaped her writing, each referred to by Emily as a tutor or master.

Moreover, Saturn signifies her obsession with death, mortality, and the tick-tock of time, echoed in the dried flowers she includes in her letters (3rd House). This resonates deeply with her Moon, as Saturn is exalted by it.

When Emily states that “Home is the definition of God,” she implies that God is neither confined to a church nor defined by it. In her worldview, God (Cancer/Moon in Libra) exalts Saturn, ruled by Mercury—Saturn governs both her 3rd House of communication and 4th House of family and ancestry. Thus, Saturn—Home—becomes a pinnacle for her intellectual Moon, which oversees her conception of God, crafting verses that reflect this profound relationship.

Saturn in Virgo diligently polishes words, constantly communicating while relating to its higher authority—God—in the 3rd House of the mind and “inner religion.” This connection draws inspiration from the expansive realms of the 9th House, representing Outer or Higher religion. Home and God form the foundation laid by her father, entwined with her neighbors in the 3rd House, including her beloved brother and platonic romantic partner, Susie. For Emily, Home becomes a sanctuary where her entire spectrum of experiences—both with and without God—unfolds, ultimately leading her to withdraw from society.

Interestingly, she never departed from what she called “my father’s house,” a poignant detail considering her Uranus in the 4th House. Uranus injects sudden motion into her life, leaning towards freedom but also adding an eccentricity characteristic of this unpredictable planet. Its antiscion closely aligns with her Ascendant, infusing her existence with unexpected mental lightning bolts. This Sky God delivers shocks through her experiences of faith, home, father, and language, allowing her to navigate her life on her own unique, Uranian terms.

Home becomes the stage where Emily experiences it all—imaginative loves, sudden losses of family members, friends, and her beloved dog, Carlo. It holds pressed flowers, a symbol of death (think Venus combust, burned up, and consumed by the Sun), alongside ethereal white dresses that eventually culminate in a white coffin. The connection of her radiant Moon, nestled in the isolated depths of the 12th House and ruling her House of God, inevitably leads to the arrival of that white coffin once the white dress is no longer needed.

She has walked in white until the darkness allowed.

I must go in, the fog is rising.

The Moons Poems of Emily Dickinson—

This pearly, intense Moon serves as a sect ruler and conjoins the mighty fixed star Arcturus, known as the star of honor. As Ptolemy notes, it bestows prosperity through effort, strong desires, a tendency toward excess, self-determination, and a fondness for rural pursuits, along with a sprinkle of occult intrigue.

Her Midheaven sits on Regulus, one of the most fortunate royal stars, signaling enduring wealth, success, and glory. This potent combination of Arcturus and Regulus bestows upon her a lasting myth. She first gains visibility through the 11th House of friends, particularly Mabel, a friend/foe and her brother’s mistress (whom she never met), who awkwardly combusts Venus by bringing her poems into the public eye.

The most significant publication of her work, [“The Poems of Emily Dickinson”], represents a complete and mostly unaltered collection of her poetry, finally available to the world in 1955 thanks to scholar Thomas H. Johnson. That year, Emily’s progressed Saturn hovered over her Midheaven, with Mercury trining it, facilitating the flow of her poems and activating her Midheaven glory. Coincidentally, she was also in her Level 2 Gemini period (of Zodiacal Releasing from Spirit), highlighting Mercury as its Lord, along with a stellium in Sagittarius (Sun, Venus, and Mercury).

Letters to Susie—

Nobody knows who Susie really was to Emily. [Were they lovers or was it only a platonic relationship?] What’s documented is that Susie was the receiver of over 300 letters Emily wrote while living a couple of yards away.

Susie was a muse, an adviser, and a significant female in her Heart (Moon / Neptune). Emily wrote:

With the exception of Shakespeare, you have told me of more knowledge than any one living.

Emily’s relationships (L7) and friendships (L11) were often fleeting, as she physically isolated herself. Her need for connection flowed through nearly 2,000 poems, hidden until after her death. Combust Mercury diligently used Saturn to craft those millions of words, preparing for its future appearance on the Midheaven.

She had to write—her Midheaven is ruled by the Sun, in conjunction with Mercury and Venus, while Mars’ antiscia/Lord of her Ascendant aligns with her Part of Spirit in Virgo. The Part of Spirit’s antiscia falls precisely between the Sun and Mercury. As per medieval astrology, this Part of the Spirit can act as an alternate Ascendant, reflecting actions, professions, and motivations. Its ruler, Mercury, squares it exactly, pushing Emily’s fountain pen through tension.

She writes:

The poet lights the light and fades away. But the light goes on and on.

End of Part One (I think…)

Make sure to see my video about Emily’s Woods below, and consider collecting “Emily’s Woods archival art print.

All artwork © by Marta Spendowska / verymarta.com